“Curriculum mapping is helping departments across UBC identify gaps or redundancies in their degree programs, and spot missed opportunities for things like how best to utilize pre-requisites,” said Allyson Rayner, a curriculum consultant at the Centre for Teaching, Learning and Technology (CTLT) who helps facilitate this process.

Curriculum mapping is a process that allows degree programs to see how individual courses within the program combine in order to scaffold students’ achievement of the expected program level outcomes across courses. It is a method used to articulate where, when and how students arrive at the learning outcomes of a program.

The process can be used to map different aspects of a program curriculum, including the level of complexity or depth to which something is covered in a program, the amount of time spent on a certain topic, the types of assessment a program uses across a four-year program, or the methods of instruction used in the various courses.

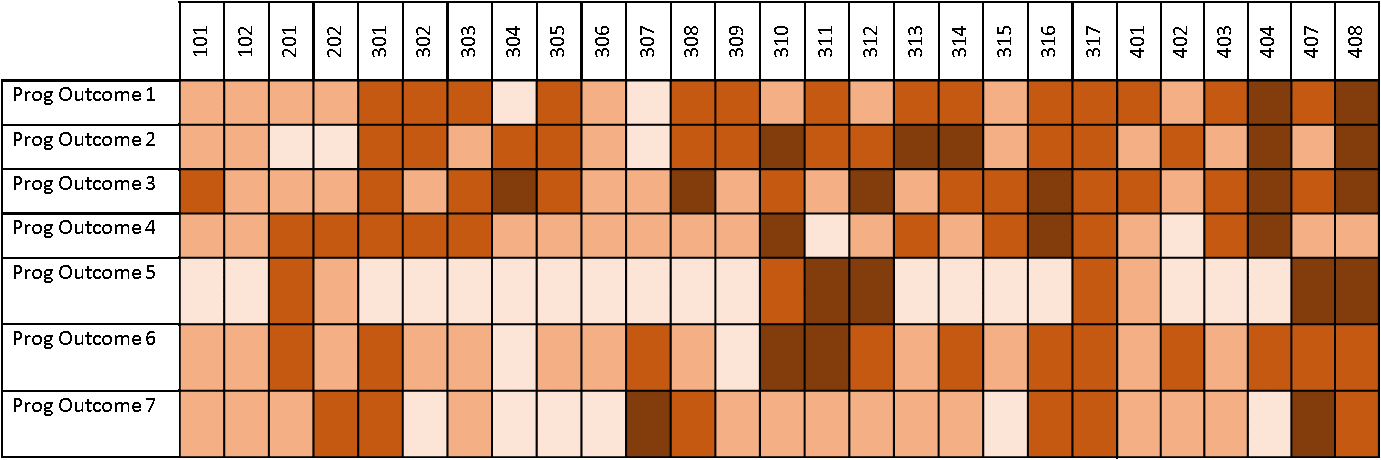

From the above curriculum map, we can see that program outcome 5 does not get a lot of coverage across the program and perhaps students need more in-class time devoted to this topic. Conversely, program outcome 3 is addressed in almost every course. Perhaps some of this energy could be re-directed to program outcome 5. Additionally, students only receive 2 opportunities to “master” program outcome 6, which raises the question of whether or not this is enough time. Many more questions can be asked of this curriculum map, these are just a few examples.

You can begin a curriculum mapping project as a way of exploring the broad structures of the curriculum which might have organically developed over many years, or you can begin with a specific question in mind. “Do you want understand how students are experiencing assessment? Do you want to understand if students are being properly scaffolded regarding a specific concept?” If the question centers on assessment, for example, then you could map the program’s assessment strategies across the years to see if students are only asked to recall/regurgitate information in their fourth year, or if students are only ever expected to write essays and never partake in any experiential learning. Once you have a complete picture of the program, than you can start to ask strategic pedagogical questions why, where and how things are taught.

The Arts Program Outcomes project

In January 2014 the Faculty of Arts rolled out the Program Outcomes project. “[The] initiative intended that each specialization in the Faculty declare its outcomes: what students would be able to do following their years of study in the discipline of their major,” said Janet Giltrow, Associate Dean in the Faculty of Arts.

She says they got amazing results. The outcomes statements showed – clearly, dramatically – what people called critical thinking in the visual arts and how different it was from critical thinking in art history or literary studies. The statements showed what made a philosophy essay a philosophy essay.

“The next natural step was to take in these statements and goals and reconcile them with the curriculum. Were students actually able to reach those goals through the courses available in the curriculum and the program? That’s where the mapping started.”

Mapping an Arts curriculum

According to Rayner, five units in the Faculty of Arts, including the Museum of Anthropology (MOA) have already undertaken curriculum mapping this year. “One of the benefits of using this tool is that it allows you to see the students’ entire complex four-year experience in one way,” said Rayner. “Psychology, for example, saw that many of their majors were taking their quantitative research methods courses in conjunction with their third year courses. Majors should be taking their methods course before their third year to prepare them for reading primary research in their third year.” Now the department is seeking to rework the pre-requisite structure and second year courses to address this need.

The result in the larger Arts project has been positive, Giltrow agrees, especially when it comes to identifying discrepancies between outcomes and program curriculums. “Programs have found that they introduce a high-value goal over and over and over again. But we can’t really see in the curriculum where students would progress to a position of expertise. The curriculum does not provide for that expertise or developing expertise,” she added.

Collecting and analyzing the data

When you’re deciding how to collect the data on curriculum mapping, there are three things to consider: the source of information, the methods for gathering the data, and the scope at which you would like to collect data.

Sources may include instructors, students, alumni and the syllabi for course. Who you choose as your source will depend on which point of view you hoped to map the curriculum. In addition, there are several different methods you can adopt for collecting information, explains Rayner. For example, content analysis of syllabi, surveys, interviews, focus groups, workshop, and e-portfolios are all possibilities.

The tool used in Arts to do the curriculum mapping is a fluid survey, and includes questions like, “Which program objectives does your course cover?” and “Describe the role of theory in building this discipline’s knowledge.” Once the answers are in, curriculum consultants at CTLT aggregate the data and create heat maps to visualize the curriculum, explains Rayner.

Expanding the use of curriculum mapping

When Giltrow talks to departments about outcomes, she asks “What kinds of questions in the world will graduates of your program be able to answer expertly and responsibly?” That question, she explains, applies to everything from psychology to art history to anthropology to economics.

“If we look at outcomes in those ways we begin to tell the story of the roles that arts disciplines play in the larger community. We haven’t done a good job of telling that story because we always revert to generalities about communication skills and critical thinking,” said Giltrow. “I think now we are beginning to gather the materials for telling that story about arts’ distinctive and definitive contributions to the communities beyond the university.”

If you’d like to know more about curriculum mapping or are interested in mapping your program’s curriculum, please contact Allyson Rayner.