At the recent 2015 CTLT Spring Institute, Robyn Leuty, Will Valley, and Kyle Nelson shared community-based experiential learning and team-based learning approaches used in the Faculty of Land and Food Systems (LFS). In LFS, students are enrolled in a core series of courses between first and fourth year, called the Land, Food and Community (LFC) series. These courses were designed to help students develop professional skills by introducing them to community-based experiential learning and team-based learning approaches.

At the recent 2015 CTLT Spring Institute, Robyn Leuty, Will Valley, and Kyle Nelson shared community-based experiential learning and team-based learning approaches used in the Faculty of Land and Food Systems (LFS). In LFS, students are enrolled in a core series of courses between first and fourth year, called the Land, Food and Community (LFC) series. These courses were designed to help students develop professional skills by introducing them to community-based experiential learning and team-based learning approaches.

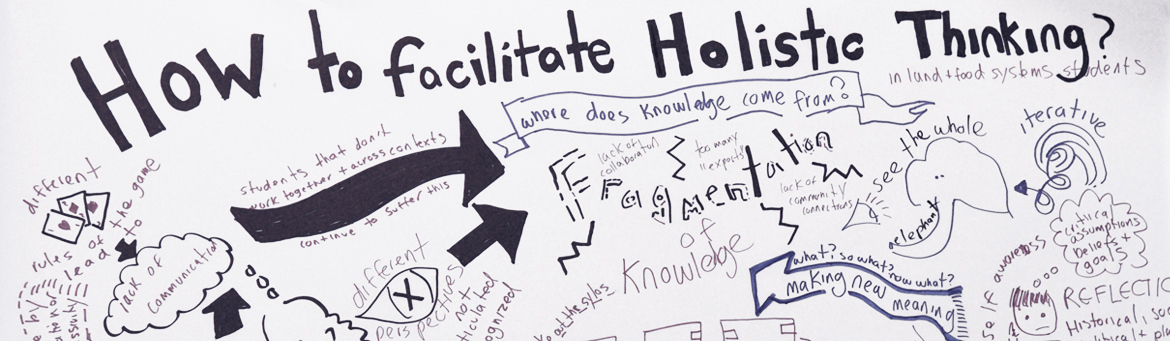

Will, an instructor in LFS and the Academic Coordinator of the LFC core series of courses, introduced a thought provoking cartoon of an elephant. Blind men were shown touching different parts of the elephant, with thought bubbles illustrating their incorrect perceptions due to a limited intake of information – the tail is a rope, the tusk is an arrow. Will used this image as an analogy for the Faculty of Land and Food Systems. The faculty is supposed to look at food systems as a whole, yet education often looks so narrowly at isolated topics. In order to overcome this fragmentation of knowledge, communication is key. It is especially vital in LFS studies because it is necessary to look at food systems as a whole to find holistic, overarching solutions: how do we feed 9 billion people without exacerbating detrimental effects on our modern food system?

The Faculty of Land and Food Systems has implemented community-based experiential learning projects in its LFC courses. In LFS 100, students volunteer with local organizations. In LFS 250 students run food literacy workshops with local students from grades K-12. In LFS 350 students organize a province-wide food security initiative and, by LFS 450, students complete a food-systems project on the UBC campus. “We want to give them an opportunity to apply knowledge in an interdisciplinary setting,” says Will. The purpose of these projects is to develop holistic, collaborative, interdisciplinary food thinkers and learners.

Robyn, a Student Engagement Advisor at the Centre for Student Involvement and Careers, has been working closely with the LFC program in order to implement a collaborative learning environment across the LFC courses. “It is about them learning from each other,” she explains. Robyn, Will, and Kyle have been using various tools throughout the LFC courses to encourage collaboration and team-based learning. “Each individual member of a group offers their whole unique perspective for the group,” explains Robyn. “We want them to be empowered to share their perspectives.” The goal is for the students to learn from each other, rather than working separately to complete a common task.

One tool that is used to encourage collaboration is the Social Change Model of Leadership. It gets students thinking about their strengths and what they can offer in a group. Robyn notes that she gets students to think about what their values are and to “focus on the values of the group.” Students start developing self-awareness, and learn to navigate other peoples’ values to facilitate collaborative learning. “Within the diversity of the group, there are a few key values that are similar,” adds Will. He explains that the focus should be on finding similar values to work towards.

StrengthsFinder is a tool used in LFS to help identify individual and group strengths. “All students in second year are exposed to this tool,” Robyn explains. StrengthsFinder is a type of aptitude test that helps identify a person’s top five strengths. “The idea is that the student learns about himself or herself so they can leverage their individual contribution to the group,” says Robyn.

Another tool that facilitates collaboration is Moments of Significant Change. Students identify a significant point in time when something shifted for them. They then describe what happened, who was involved, and what the environment was like. This is done in order to create awareness for how the student was feeling at a certain time during a community-based project. These individual stories help define the collective experience, and help tell the collective story. Robyn then gets the students to think more broadly about the collective experience “What does the collective story tell, and what do you want the next part to tell?” She also encourages them to come back to community values and purpose, and re-evaluate them. “[The students] establish together what they wanted the group outcome to be,” Robyn explains. This helps them collaborate over shared passions to achieve this common purpose.

The LFC courses also involve a critical reflection component, where students can reflect about their learning experiences. Critical reflection involves describing, connecting, re-evaluating, and reworking, according to Kyle, Officer, Community-Based Experiential Learning, with the Faculty of Land and Food Systems and the Centre for Community Engaged Learning. Kyle explains that the purpose of critical reflection is “connecting self with experience.” With the community-based experiential learning projects, students are encouraged to reflect about their experiences. Kyle explains that the “learning by teaching model” is used with food literacy workshops in second year. “Third year students work with a community centre in the Downtown Eastside,” adds Kyle, and critical reflection brings to light political issues of social justice and equity. “They see the day-to-day activities and values of the community,” adds Kyle. “They saw a community partner struggling with these issues.” In fourth year, students reflect about leadership and connect it with the community. According to Kyle, they undergo a “critical examination of where knowledge comes from.” He also noted that a lot of students have an aversion to leadership, and critical reflection challenges students to think about diverse ways of leading. Robyn adds that it challenges “conceptual notions of leadership…How did you show up as a leader?”

With the LFC series, Will stressed that students are encouraged to develop interdisciplinary, systems thinking competencies, in a collaborative learning environment. “We want to help create future professionals that can work in an interdisciplinary setting,” explains Will. “We need more and more collaboration between disciplines.” He hopes to open up more portions of the courses to the community partners, and notes that the community partnerships are key components to the courses. Community-based experiential learning allows students to see how their actions have an impact on society, beyond the classroom.