Rewarding integrity: Changing the conversation on cheating

Whether you call it ‘cheating’, ‘plagiarism’, or ‘breaches of academic integrity’, as long as there’s been academia there have been those accused of misconduct. With increases in our usage of learning technologies, this already complex matter has only been complicated further.

The topic is receiving increased attention across the higher education landscape. Here at UBC, it was featured as one of UBC’s Guiding Principles for Online Teaching, saw the 2021 appointment of an Academic Integrity Senior Manager in the UBC Vancouver Office of the Provost and Vice-President Academic, and this fall included the launch of UBC’s first-ever celebration of Academic Integrity week.

Dr. Laurie McNeill is one of UBC’s prominent voices on academic integrity, as well as a professor of teaching in the Department of English Language and Literatures, and the former Director of First-Year & Interdisciplinary Programs. She shares the personal journey that took her from “busting cheaters” to a more educative approach, and keeping “dynamic generosity” alive in an ever-evolving academic landscape.

Addressing the information gap

Despite the wide-reaching implications and high institutional priority of academic integrity, part of what makes it such a challenging topic are the personal considerations. For instructors and students alike, the underlying emotional stakes are an important piece of what makes this issue so complex.

Like many, Laurie’s work in this space started as a personal journey, beginning with a “transformative” series of encounters with students. She explains, “for 10-plus years I was an instructor in literature, and I had a great track record for ‘busting cheaters’, and I was really quite proud of that record of ‘catches’.”

But as she moved to a more administrative role as a program director, she became responsible for disciplinary meetings with these students. And she was surprised to realize that in many cases, the students simply did not understand the core principles of academic integrity. While Laurie and her colleagues thought they were encompassing concepts like citation and belonging to the scholarly community in their teaching, she found “it was very clear that the students had no idea why we cared about academic integrity. It was just a random rule; there was no sense of why it mattered. And as a result, we were punishing them without having taken up that responsibility of educating them on what it was that they’d done wrong.”

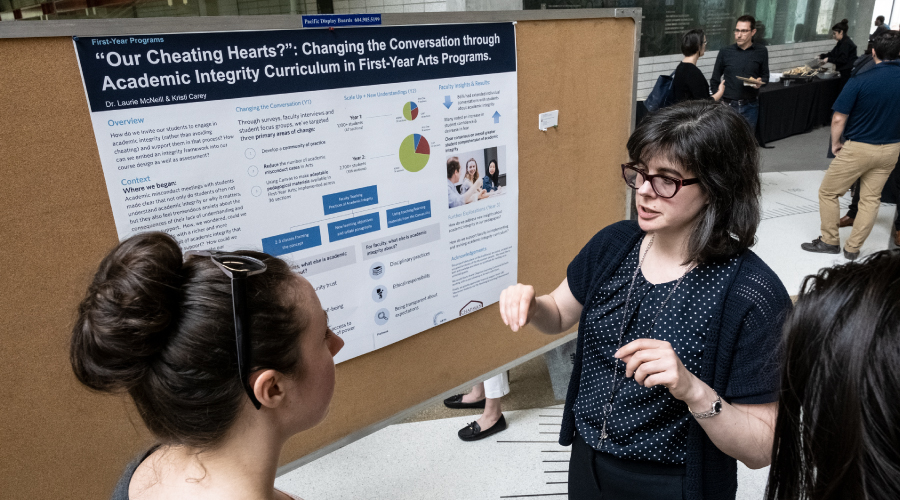

Dr. Laurie McNeill presenting her Teaching and Learning Enhancement Fund project Our Cheating Hearts.

This educative approach was at the core of the Teaching and Learning Enhancement Fund project Our Cheating Hearts, which Laurie launched in 2017 in partnership with the Chapman Learning Commons. Initially a pilot project to incorporate academic integrity materials into the curricula of selected first-year writing courses in the Faculty of Arts, it proved so successful that it was rolled out across all Arts’ First-Year Arts Programs core courses (ASTU 100, WRDS 150, and Arts One) the following year. To further the conversation and share these successes with other students and faculty members, the project then evolved to develop a suite of resources to support teaching academic integrity, including sample material and a Canvas module that can be shared directly with students.

Shared values and shifting the model

Despite the success of the project and its compassionate underpinnings, Laurie knows that no approach or method can completely remove all academic misconduct. “One of the things I’ve had to remind myself is that the point is not to eradicate cheating,” she explains, “because that’s not going to happen.” Like so many instructors, she’s experienced this disappointment first-hand — describing the discovery of her course materials on a ‘homework help’ website earlier in the year as “a bit of a burn.”

She points to the way that new learning technologies have further complicated the dynamic of students seeking academic shortcuts and instructors enforcing academic integrity. Particularly with the rapid move toward online teaching and learning, websites billing themselves as ‘homework support services’ have, it’s been suggested, deliberately confused the issue in order to increase uptake of their services.

But Laurie explains that this hasn’t undermined her approach, pointing out that often, there’s a tendency in discussions about academic misconduct to focus on a “default deficit model” that fixates on what’s gone wrong. “I should think about — we should all think about — how many students didn’t commit academic misconduct.” This shift in framing extends to how academic integrity is taught to students, too; she suggests that we aim to “create a space in which we reward integrity, because that’s going to help more students understand what this means.”

“We don’t see our students in all the decision-making moments,” Laurie explains. “But ideally, what we do is just give them a framework to step into that means something to them, and then becomes part of their ways of working.”

Making space for understanding

While addressing students’ understanding of academic misconduct is an important factor in preventing it, there are other dimensions to consider. Principle 5 in UBC’s Guiding Principles for Online Teaching calls attention to the body of research demonstrating that “breaches such as cheating and plagiarism are most typically the result of feelings of desperation, plus opportunity”. This is echoed across other work at UBC in the academic integrity space — such as the academic integrity triad shared by UBC Faculty of Applied Science’s Peter Ostafichuk in his Remote Assessment Guidebook. Here, the likelihood of academic misconduct is influenced by three dimensions: pressure, opportunity and rationalization.

Rationalization can be supported through improving student understanding, but the pressures and opportunities students face include more than just what takes place in the classroom. Laurie reflects that of the students sent to her for her to investigate misconduct, “a lot of them were ending up there who were in crisis, or who just didn’t understand how the university worked. Which,” she notes wryly, “seems like an unfair way to end up arriving at the place where you find someone who is willing to help you.”

Through the rapid shift to fully-remote teaching and learning, and our subsequent transition back to the campus environment, students continue to face an array of changing pressures and opportunities. But the guidebook and Laurie both suggest that when students understand and value academic integrity, they are less likely to engage in misconduct even when the other dimensions increase.

For Laurie, addressing assumptions about what students already know and ensuring their understanding ties into the idea of ethical, accessible classrooms. “In some ways, my academic integrity approach has been about equity and accessibility — in the sense that making these ideas explicit, and opening up space for conversation, for questions, makes them accessible to all students,” she explains.

By incorporating academic integrity in an open and educative way, “it’s allowed us to think about the ethical space of teaching — to create a more inclusive, more accessible space, where we give all students the knowledge and understanding and rationale for what is a really foundational aspect of our identity as scholars.”

More broadly, she reflects that “while teaching online, we had to rethink accessibility writ large in all kinds of ways,” leading with compassion to support students’ individual circumstances. “And I think that now that we have returned primarily to on-campus teaching, in an ideal situation we would continue to recognize and make spaces and ways of working that offer accommodation.”

As academic integrity increasingly is incorporated into teaching and learning strategies at UBC, more practitioners are modelling and sharing these principles. Just as approaches to teaching methodologies and technologies need to continue to change and adapt, Laurie suggests that “academic integrity, or ‘pedagogies of integrity’ as I call them, have to be dynamic and responsive” to the teaching and learning environment.

One thing that remains core to Laurie’s approach to academic integrity, and that she hopes she and we all will carry forward, is working to “have a sense of dynamic generosity, towards our students, but also towards ourselves, and towards our colleagues; appreciating that it’s a lot of hard work in a year that was already a lot of hard work. That generosity is a quality I would like to maintain.”

More stories

The transition to online: One year later

To introduce the series, Associate Provost, Teaching and Learning Dr. Simon Bates and Provost Office Fellows in Online Learning Dr. Catherine Rawn and Kieran Forde reflect on UBC’s transition to online teaching.

Bringing compassion to the online learning environment

In this story, learn how two members of the teaching and learning community relied on compassion and care to create memorable learning experiences for students.

Sharing community values from a distance

The Haida Gwaii Institute team explains how they relied on their community values to provide experiential and transformative learning opportunities from a distance.

Experiential lab learning: stories from a year of online teaching

In this story, three instructors from the Faculty of Science explain how they took the challenge of online teaching and turned it into an opportunity to experiment with learning.

Bridging the accessibility gap through Universal Design for Learning

In this story, two instructors with previous experience with online teaching share their experience and tips on the key aspects to consider when implementing Universal Learning for Design (UDL) into a course.