Bridging the accessibility gap through Universal Design for Learning

With teaching and learning shifting to be primarily on campus this fall, many instructors have had to rethink again what teaching looks like. Should they close the parenthesis of online instruction and resume teaching as usual? What about students who discovered improvements to the way they learn, thanks to the flexibility of accessing resources remotely?

Accessibility is a major theme in this discussion, as digital course materials can be a tremendous asset for all students — or create bigger hurdles and inequality of access because of the technology used.

Although it has been used since the 1990s, the concept of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) recently took center stage in helping instructors transition to fully online teaching, and it can be a great asset in the transition back to campus. As early adopters, two instructors who taught online before and during the pandemic share their experiences and tips on the key aspects to consider when implementing UDL into a course.

Including accessibility from the design stage

UDL is an approach to curriculum development that minimizes barriers and maximizes learning opportunities for students. At its core, it relies on designing a curriculum that can be used and understood by everyone. Rather than putting the learner in a passive position, UDL relies on three core pillars of learning: to address what, how, and why we learn. Finally, it is flexible enough to adapt to many students’ needs.

In the context of UDL, barriers are not limited to designing resources for people with accessibility needs in mind. The benefits of UDL are not only for people with limited technical or Internet access. It also helps for those juggling work, or, more broadly, people who cannot attend in-person classes. This past year, because of COVID-19, that meant virtually everyone.

Accessibility features must be included from the design phase of a course to maximize learning opportunities for students.

For Penny Hatzimanolakis, lecturer in the Department of Dentistry, UDL is a topic she has been interested in for a long time. “I’m always reaching out to experts, such as Afsaneh Sharif from the Centre for Teaching, Learning and Technology (CTLT), asking her what is new, what is changing, and how to make courses more inclusive and diversified, especially online.” Together, Penny and Afsaneh have implemented UDL practices in Penny’s courses to accommodate her students’ diversity, from using videos with closed captions to introduce her course, to providing alternative assessments.

Robert Russo, lecturer at the Allard School of Law, is also a strong believer in UDL in the classroom. “Even before the pandemic I tried to design my classes for online delivery through electronic materials whenever possible,” he reflects. Having taught online to students needing accessibility features in the past, he is well aware of the benefits of providing as many ways to access his course as possible. “From enabling Zoom transcriptions, to using a lot of imagery with descriptions, to adding other resources such as PowerPoint presentations or designing virtual video tours of the course, I try to give my students many different ways to look at the same topic.”

Keeping the course design simple

Adjusting courses to incorporate UDL principles does not have to mean starting over. Both instructors agree, even slight changes can make a big difference, as long as simplicity is a guiding force.

When asked about common mistakes to avoid, Penny and Robert insisted on the importance of not transcribing in-person resources literally for online delivery, for everybody’s sake. “A couple of my colleagues exhausted themselves spending too much time on Zoom and putting too much content online,” explains Robert. “They were essentially preparing two courses — one over Zoom, and another one through Canvas.” Rather, both Penny and Robert recommend focusing on keeping courses simple and centralized through platforms like Canvas, while ensuring class materials are accessible to all students.

One of the first changes Robert made to his courses was to adjust their structure so that lecture hours would not directly translate into Zoom sessions, but rather would compose one part of an extended discussion. “If a class was supposed to have six hours of lecture time in a week, instead of doing six hours of Zoom — which for me is too much — I would only do two hours over Zoom, and then I’d translate the discussions we would have in class into an online forum on Canvas, so that students could interact there.”

For Penny, who had previous experience teaching online and offline at the same time, simplicity and flexibility are two key elements of her approach to UDL. “This past year, I recorded humorous videos of myself to create a positive atmosphere and stay connected with my students while online. Just smiling and letting them know that I was here for them goes a long way in making everybody feel safe and included.” She also applied flexibility to her students’ presentations, giving them the freedom to choose the delivery method that best suited them. “Some students prefer oral to written presentations. If it is a block activity, they could respond via video with closed captions if they chose to. It didn’t have to be complicated in design; what mattered was engaging with the course in a way that resonated with them.”

However, even though Penny and Robert believe in UDL as a way to provide learning opportunities for all, they both acknowledge that the process is not without challenges.

Managing resources, student needs and expectations

When it comes to transitioning to UDL, not all courses are created equal, especially regarding readily available resources. “The problem we found is that a lot of textbooks are still only in paper format,” explains Robert. “Especially since the pandemic, I was trying to get more electronic materials and it was a surprise to me how many publishers don’t offer electronic versions of their textbooks, which is unfortunate.”

Penny found herself in a similar situation, having to prepare for what would have been an in-person session to an online dentistry course.

“I was surprised that, even for fundamental notions such as tooth development, there weren’t that many well-developed videos for the current learner in mind or other easily accessible interactive formats on the subject. You can read textbooks and discuss online but to support the diversity of students’ learning with such complex theories, new dental “language” and the devices to which they are learning from, requires a hybrid approach.”

Another challenge that often gets lost when addressing UDL is that its implementation occurred during a pandemic, which dramatically impacted how knowledge is shared. As a result, during this time UDL might have been perceived more as a replacement to in-person teaching rather than a way to maximize learning, regardless of the format — online, in-person, or hybrid.

As Robert points out, “it is different when you are teaching in an online environment where it is not necessarily by choice. When I was teaching online courses in the past, I had students who chose distance education courses intentionally. They knew what to expect, especially regarding synchronous vs. asynchronous classes.”

When describing their experiences, Penny and Robert noticed the need for some sense of normalcy in their cohorts, especially for first-year students. “They are UBC students, yet they had never stepped a foot at the university, which was difficult for them,” Penny explains. “They needed more ongoing communication — as if they were on-campus — because this is where they were supposed to be!”

The versatility of UDL, thanks to the many ways it can be adjusted, played a big part in making the most out of a challenging situation.

For Robert’s students, the need for a more traditional structure despite learning online came with the expectation that some of his courses would remain synchronous. “In this situation that we are hopefully coming out of, many of my students expected this synchronous time because they did not choose to learn from home asynchronously. My challenge was how to do that without spending too much time on Zoom,” he explains. “It was an interesting learning experience for me, but after doing it for a year-and-a-half, it is a combination that can work for different modes of learning thanks to UDL and technology.”

When reflecting on this strange period – even for instructors with previous online teaching experience — both Robert and Penny shared the belief that technology and UDL can be powerful tools that need to be used carefully.

“This past year has been good, all things considered. It has given me a different perspective on the many ways to do online learning,” Robert concludes, happy to see his colleagues using tools for which he has been advocating for a long time. “I think pandemic-teaching raised a lot of awareness that tools exist and that they can be used even when we are back on campus. Hopefully these resources will be maintained, if for nothing else, to allow students to access resources through Canvas, without having to purchase everything in a hardcopy format.”

Penny agrees that there have been some benefits to teaching during the pandemic in terms of education and pedagogy, and that UDL can accommodate even the most uncommon circumstances. However, she is mindful of its limits in a fully-online context. “One of the downsides I can see is that the pendulum swings too far the other way — with pre-reading assignments, asynchronous sessions, etc. — where students would end up having to teach themselves, which is not right either. The most important take away for me is to ensure we are not creating expert students, but rather expert learners, having an open mindset and making the material their own.”

Only time will tell how the future of teaching and learning will look in the future. However, whether applied to an online, on-campus or hybrid context, it looks very likely that the use of technology through UDL is here to stay.

Are you interested in implementing Universal Design for Learning into your courses? Get in touch with an expert from the CTLT.

For more on UDL, check out this recent article highlighted in Edubytes, the CTLT’s monthly newsletter featuring emerging trends in teaching and learning in higher education.

More stories

The transition to online: One year later

To introduce the series, Associate Provost, Teaching and Learning Dr. Simon Bates and Provost Office Fellows in Online Learning Dr. Catherine Rawn and Kieran Forde reflect on UBC’s transition to online teaching.

Bringing compassion to the online learning environment

In this story, learn how two members of the teaching and learning community relied on compassion and care to create memorable learning experiences for students.

Sharing community values from a distance

The Haida Gwaii Institute team explains how they relied on their community values to provide experiential and transformative learning opportunities from a distance.

Experiential lab learning: stories from a year of online teaching

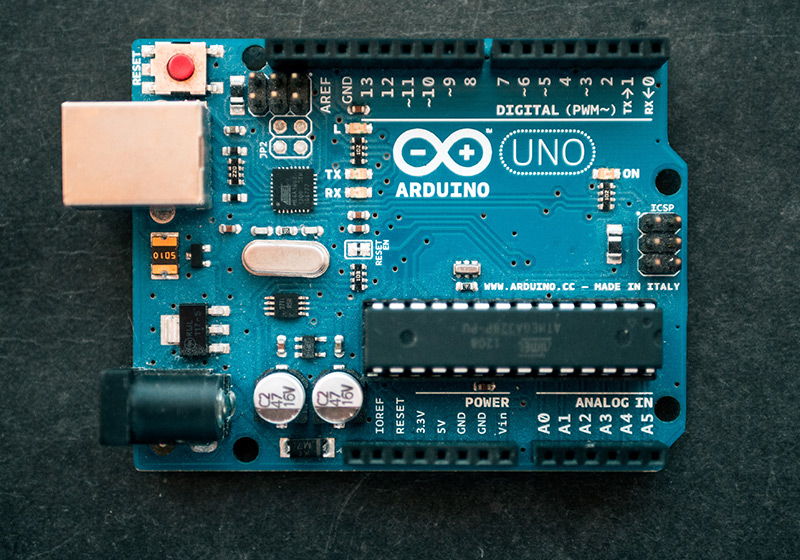

In this story, three instructors from the Faculty of Science explain how they took the challenge of online teaching and turned it into an opportunity to experiment with learning.

Rewarding integrity: Changing the conversation on cheating

In this story, Dr. Laurie McNeill shares the personal journey that took her from “busting cheaters” to a more educative approach to academic integrity.